Simla 'below Cart Road': Biographies of houses in the margins of an Imperial urban age

by Ayona Datta

After three months, we finally receive permission to access the Shimla Municipal Corporation (MC) Records Room. We walk down the four flights of stairs from Cart Road to the basement of the Car Parking building. There, hidden away from tourist view, is the Records Room. The staff are bemused that we are interested in Shimla’s colonial history; they kindly hand us the master registers with a catalogue of file names and descriptions maintained since mid-nineteenth century, from where we identify file numbers which the staff fetch for us. The Records Room itself is a visual and olfactory overload - from the packed shelves with files falling off them, tattered files strewn across the floor, files kept rolled up in cloth, alongside the smell of damp, dust and rodents – we are overwhelmed with the ruins of history in front of us. The staff though seem to find every file we request with precision, and are meticulous about returning these to the shelves.

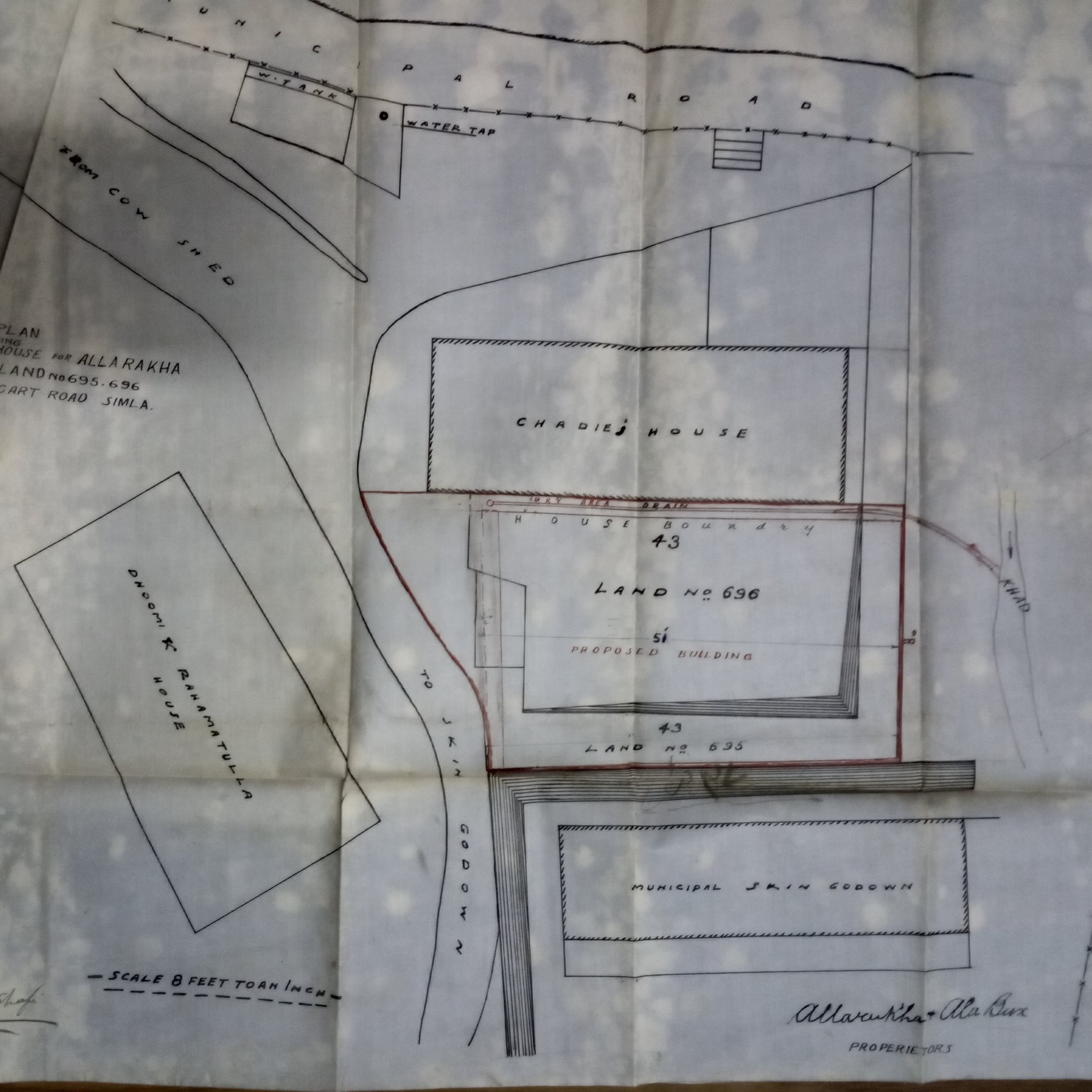

When we start reading the files, we do not know what to expect. As we tenderly open each file, some of them literally begin to show the test of time – half-eaten by rodents, droppings falling off pages that are often threadbare. Each file contains a chronicle of building applications on a particular house in Shimla (spelt as Simla during the British Empire), which was being built, approved, inspected, demolished, rebuilt and recorded meticulously by the Simla Municipality since the late 19th century. In some cases, the files contained intricate hand-drawn plans, elevations and sections of houses that applied for planning permission from the Municipality. This was a curated history of Simla’s ordinary urbanism.

In 1911, Abdulla Contractor applied to Simla Municipality to build an Imambara (small mosque) for Shia Muslims in ‘Ladakhi Mohalla’. Signing off as ‘Your most obedient servant’ he assured that this building was only for religious activities. This was subsequently granted, although the Resident Engineer writes a memo to the Assistant Secretary that ‘it is a mistake’ since Municipal Corporation (MC) has refused similar applications in view that the future of the area is uncertain. Abdulla therefore gives an undertaking on stamped legal paper that the proposed Imam Bara would only be used for religious purposes and that he, his successors/heirs or any representatives of the Shia/Sunni community will have no rights to the Imam Bara if the MC needs to acquire it in the future. Three years later, the Resident Engineer found that Abdulla was in breach of this agreement. One room of the Imam Bara was being rented out to five ‘Ladakhi coolies’ and another was being used as stable. In his memo to the Assistant Secretary, the Engineer writes, ‘I think surprise inspection is necessary”. (12/8/1914). The MC immediately initiates an injunction against Abdulla, who argues that the lower floor is occupied only by a ‘Caretaker’. The MC responds that unless a window is provided, it will not be deemed fit for human habitation. Abdulla promptly adds a window and so begins the cycle of transformation of the Imambara slowly into a residential property. New owners in 1932 demolish the Imambara and in its place build a three-storey residential house with basement quarters for coolies.

From the late 19th to early 20th century, Simla was undergoing rapid urbanization. The British had declared it as its Summer Capital and set up the Simla Municipality in 1851. The Imperial buildings and residences were constructed on the upper slopes of the hill, on the Ridge and the Mall road. Below that in middle and lower bazaar emerged the commercial centre. But along the lowest slopes of the hill settled the Muslims and lower castes – the workers who fed, cleaned and clothed the Empire. As they were not allowed to own land or property in the upper slopes, Simla’s lower slopes provided much needed spaces for working class houses, godowns for building materials, religious buildings, coolie quarters and cattle sheds which were rapidly built with approval from the Simla Municipality. These became what the Municipality often labelled as ‘bazaar area’ ‘congested’, ‘unsanitary’, a ‘rabbit warren’ and with ‘uncertain future’. These notions of dirt, hygiene and danger associated with the lower slopes led to the formulation of the Simla Improvement Trust (SIT) which proposed the demolition and reordering of the area much like the Victorian slum improvement schemes in England.

A cosmopolitan biography of ordinary houses from ‘below’

In the record room files, the lowest slopes are referred as ‘below Cart Road’. In the early years of the Imperial capital, ‘below’ Cart road appears as a placeholder. All other places above Cart road have already been named – Ridge, Mall Road, Gunj Bazaar, Lawrence Gunj, Edwards Gunj and so on. Below Cart road consists of the following landmarks – Slaughter house [abattoir], [animal] Skin godown, a ‘Hindoo’ [children’s] graveyard, a Serai (or horse stables) and ‘Ladakhi Mohalla’ a neighbourhood built around the Imambara by Shia migrants from Ladakh in North India. Later, another neighbourhood ‘Baltistani Mohalla’ emerged to its East, referring to houses built by an ethnic group of Muslims from north of Ladakh. Around the same time a ‘Singh Sabha’ was built on Cart Road to cater to the Sikh households also settling ‘below Cart road’.

As we open each file we look through a small window into early urbanization in Simla, told to us by the incremental stories of these ordinary houses built by migrants, who came to Simla to work as coolies, butchers, tailors, blacksmiths, sweepers, and shoemakers. As an imperial capital, Simla attracted migrants from across India looking for secure livelihoods and futures. The house biographies reflect the personalities of their owners – their family life, livelihoods, economic hardships or rising prosperity. Each file reveals a biography of ordinary houses built against all odds – social, cultural, administrative and topographical. Each house starts its life as a small one room dwelling, then the owner applies to the MC to add another room, then a verandah, then an upper storey, then a toilet and so on till the mid 20th century by when these become multi-room residential buildings with kitchen and latrine and sometimes occupied by multiple families on rent. Often unauthorized constructions were made as variations in sanctioned plans, which were picked up by the MC who at times fined and even prosecuted owners.

One particular file called ‘Kalicharan’s House’ stands out. It is the only one which does not mention an occupation for its owner and includes a faded B&W photo of the house from the early 20th century. It seems that Kalicharan was a Bengali who tried to convince the MC for some time that the house with unauthorized additions was not his. Memos between the engineer, the health officer and the Assistant secretary reflect a confusion for some time. By the time, the MC checks all their records and finds out that the house was indeed in Kalicharan’s name, he had already subdivided the plot and sold them off. After a protracted period of injunctions, demolitions and criminal lawsuit by the MC he was fined Rs 50/- by the Simla High Court.

What emerges from these house biographies is a cosmopolitan history of Simla’s slopes that has been obscured by the imperial stories of grandeur at the top of the hill, by colonial and post-colonial historians alike. Biographies of houses from below Cart road right down to the graveyard near the sewers at the bottom, tell us how ordinary Simla was built laboriously, slowly and incrementally by working-class Muslims and lower castes. This is clear from the applications which are signed with fingerprints (indicating illiteracy) or with rudimentary handwriting in Urdu, and because last names are invariably given as owners’ occupation. Over time, it is clear that these owners become more prosperous with Simla’s rising prosperity. For eg. AllahBux Butcher, who in 1886 builds his home near the Slaughter house where he is working, finally owns a shop on the Mall road after 20 years where he imports British shoes and boots for the consumption of Simla’s elite. Kalicharan’s family is not that successful – repeatedly fined or prosecuted for unauthorized constructions, and having subdivided and sold most of his property, his son sells off what remains of the house in the 1960s.

It is striking that on the site plans of applications, each house is located relative to another house, and to prominent landmarks such as the Slaughter House, Serai or Imambara. Kalicharan’s house near Slaughter house for eg. is shown in the site plan as next to AllahBux Butcher’s house. Abdulla Tailor’s house is shown next to Kalicharan’s house. Each house can only be found if you know where their neighbour’s house is located, and in so doing each house is tied to others through an intricate thread of correlation and co-dependence. This is an analogue format of networked connectivity in Simla’s early days.

As we turn the pages, we often see a gap in house biographies for 10-15 years between 1940s and 50s. When we see accounts again, the names have changed. The Muslim names are replaced by Hindu names reflecting the wider geopolitics of partition of British India along religious lines in 1947. The Muslim owners either left in a hurry or sold off their properties to migrate to Pakistan; incoming Hindu refugees either bought these houses or were allocated these by the state in compensation for losing their property in Pakistan. Simla’s ‘below Cart road’ is now ‘Krishnanagar’ – a new name, a new identity. Each house now has a number. They stand alone as individual addresses, not in relation to each other.

Textual Cartography in Krishna Nagar

Why should we care about house biographies apart from a general curiosity? What relevance do these biographies hold beyond a history of settlement during the colonial period? Why are they significant for understanding and intervening in the contemporary urban age?

Looking down the slope. PC: Ayona Datta

Today we are again at the crossroads of the future of ‘below Cart road’ – aka Krishna Nagar. New proposals for Smart Cities mission development have imagined radical transformations for Krishna Nagar in the coming years – demolition and rebuilding (Shimla SCP Proposal 2017). The proposals include a new masterplan providing hotels, commercial development, and service apartments alongside basic infrastructure, open spaces and a government run ‘Smart School’ in Krishna Nagar. This radical reimagination of Krishna Nagar is not unlike the early 20th century proposals of the Simla Improvement Trust (SIT) which never materialised since the scale and size of disruption was far beyond the capacity of the municipality at the time. Yet proposals to demolish and rebuild Krishna Nagar have continued after independence in 1947 as new waves of migrants have settled there making their homes on the shifting slopes ‘below’ Cart road even as the Municipality has struggled to keep account of the rapid pace of construction activity there.

As we continue to delve into the accounts of house building, a bigger picture begins to emerge – a contentious politics of municipal regulation, planning and governance in the face of rapid urbanization – a story that extends from colonial to postcolonial contexts. The desire to reorder Krishna Nagar continues to be part of a wider imagination of this place as a ‘slum’– one that should ‘be bombed out of the face of earth’ as one of our elite respondents said to us. Even academic research on Krishna nagar has represented it through the rhetoric of risk and danger showing little understanding of its history or genealogy. Yet the house biographies reveal that the taxonomies of il/legality and un/authorized constructions are far more complicated that its denotation as a ‘slum’ below Cart road. The biographies suggest that each house has been through cycles of authorization, building, encroachments, subdivision, rebuilding, demolition, regularization, and so on since the 19th century. Krishna Nagar may have poor or absent infrastructure, but the messiness of property rights and regularization certificates make clear determination of il/legality impossible and its label as a ‘slum’ deeply problematic.

Unlike the way that our navigation of the city is now ordered by Google maps, house biographies present us with a very different order of relational and temporal maps that visualise a critical cartography from below. They do not provide us with the geolocated pins of Google, rather with stories of poverty, affluence, neighbourly politics and family life that are part of locating these houses using landmarks. These biographies are maps of time that are rich with navigational insights – they urge us to look deeper into Simla’s reliance as an imperial Capital above, on the labouring classes who were literally building its foundations by cutting into the hill slopes below. These biographies visualise the continuous struggles for space and legitimacy amongst the working classes, and thus also provide a historiography of postcolonial planning in small cities. In the imagination of a smart urban future, these house biographies remind us that Shimla’s current tourist spectacle on Mall Road above is made possible because of the continued house building by the poor and working classes below, down in the slopes, and in the margins since the dawn of the Empire.